The Uncounted

I lost my father to COVID-19 four years ago. His passing, along with those of over four million others in India, has slipped through the cracks of the country's collective memory.

Four years ago, I lost my father to COVID-19. It is a tragedy that continues to shape and, in many ways, define my life. I come from spaces where death is typically understood as a quieter affair, rooted in natural causes, and occurring in the (relative) comforts of home. Prolonged illnesses, though not that uncommon, lead to deaths in private rooms in hospitals or hospices. My father’s death in the pandemic fractured these conventions.

The COVID-19 pandemic altered lives and ways of living around the world. An overwhelming majority of the world survived the novel virus that originated in Wuhan. The official cumulative death toll, as I write this, stands at 7.1 million people globally. There is broad consensus that this is a gross undercount. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates nearly 15 million excess deaths globally in 2020 and 2021. Other estimates are even higher, including one from The Economist putting the number at 17.7 million. In all country-disaggregated estimates, leading the chart is my country, India—with at least four million excess deaths. According to the Union government, however, the total number of deaths officially attributed to COVID-19 since the onset of the pandemic in March 2020 is just a little over half a million.

After accounting for excess deaths, more than 99.75% of people survived the novel virus. Survivors included those who contracted the virus and recovered, those who got the vaccine in time and avoided a worse outcome, those who returned from the liminal space of a ventilator coma in an ICU and, those who never got exposed to the virus. No matter what category the outcome falls into, my father did not survive the virus—and we did. So now, as the families and the bereaved, we constitute a quiet society, suspended between the world of the living and the world of the dead. Writing just days after the global lockdowns were announced in 2020, Indian writer Arundhati Roy delivered a declaration: that the pandemic is a portal, telling us that pandemics had historically forced humans to break with the past and reimagine the world. And so, four years later, out of that portal we emerge—without our loved ones, with a shaken understanding of what the world is. That the world has moved on feels, at once, like a personal affront and a strange relief: that the darkest hours of our lives are behind us, even as our pain remains wholly unresolved.

No one wants to be reminded of the pandemic. Broadly, society’s accounting of the pain and burden of that time rests on a kind of deliberate amnesia. Masking, vaccines, and social distancing—when mentioned and practiced—evoke visceral reactions, and often outright mockery and derision. The language of public health has become politically fraught. There are a few reasons for this. For many, the months of the pandemic blur into a fog of loss, fear, and restriction. Months were spent in isolation, marked by mental health crises, economic uncertainty, domestic tension, and the collapse of social rituals. Weddings were postponed. Funerals took place over Zoom. Births, deaths, graduations—all unmarked and unheld. The global disruption was total, and various kinds of grief remained private and unprocessed. Perhaps the scale of collective trauma was so great that ‘remembering’ demands more than most can bear. The insistence on productivity—the unrelenting drive to “return to normal”— eclipsed the time and effort needed to understand what humanity endured. In any case, selective amnesia has become, for many, a means of survival.

If you lost a loved one in the pandemic, though, it is altogether different when you find yourself becoming an agent of forgetfulness. For one, you cannot easily detach from the omnipresent miasma of grief that is unleashed when you lose a loving parent. In our family, the months of March to June (now remembered nationally as the “Second Wave” or the “Delta Wave”, due to the stronger Delta variant) live on as a kind of private calendar. The brain, to protect itself, develops extraordinary ways of coping in the aftermath of tragedy. And yet, if I try, I can recall it all with unnerving clarity. The moment the oxygen ran out in the hospital and we scurried for cylinders. The hopeful scan that gave us a day’s worth of relief. The churn of ICU entries and exits. The last day I held his hand (Father’s Day). And finally, the day he was intubated, never to wake again.

My father spent sixty-seven days across three hospitals before succumbing to a secondary infection. He endured the worst of India’s Delta wave, which killed hundreds of thousands. He lived through black-market scams for essential drugs, the desperate scramble for oxygen, the triage lines, and the waiting-room battles for beds that left people dying in ambulances and parking lots. During those days, my sister Yasha and I often slept outside a public hospital, on the footpath—watching bodies being taken away, listening to blood-curdling screams as families were told their loved ones were gone.

If you’ve been trained in any kind of empirical science, the question of how lives become representations—and eventually numbers—crosses your mind from time to time. Lives are flattened into datasets through data collection, modified and crunched to reveal knowledge upon which precedents or insights might be formed. That knowledge, hopefully, then changes people’s lives. Consider the metaphor of a tuple. In a relational database or a spreadsheet, a tuple, in a sense, is how a life gets turned into a row of information. Imagine a table with predefined columns: name, age, diagnosis, time of admission, clinical outcome. A tuple populates that table with real values. It becomes the formal life story of a citizen, captured through data collection, verification, and curation. A tuple, once created, has its own afterlife. It is used to govern, analyze, and historicize.

When he died, after many weeks in the hospital, my father’s medical certificate listed the cause of death as “cardiac arrest.” Which means he did not even have the privilege of being a constituent in a sum, let alone a tuple. He does not exist in the grand summation of the half a million deaths the Government of India officially recognizes. His death—like so many others—was never counted.

April in Delhi

Our family of five got infected in mid-April. On the first day, we noticed a tingling in our throats. The next day, all foods tasted bland—our smell and taste were gone. It happened to one person, then two, and then all of us, inside our three-bedroom apartment in northwest Delhi. The oximeter and medicines had been stored in the house for good measure, and—funnily—I’d felt a small sense of pride that we were prepared. For the most part, we hoped we would ride it out without incident. Doctors recommended little more than paracetamol—and, ironically, the now-debunked and grossly overprescribed Ivermectin, which had gained traction among anti-pharma skeptics as a miracle drug despite no evidence of its efficacy for COVID-19. Additionally, my father turned to Ayurveda—the millennia-old system of herbal, ritual, and dietary medicine—whose efficacy he, like many, trusted instinctively. He began consuming various concoctions and home remedies as supplemental therapy—including formulations with no proven medical benefit, but nevertheless recommended in official protocols released by India’s health ministry.

All throughout, it was my mother’s illness that had concerned us. On Day 10, we ran out of antipyretics, Ayurveda supplements, and even the Ivermectin. That same day, my mother had fallen into a near-catatonic state due to respiratory stress. Her oxygen levels were now hovering in the 80s, even while we kept her in the prone position—something we’d learned from medical advisories on television and WhatsApp.

The roles between our parents and their children had been reversed: my sisters and I were now the caregivers, the decision-makers, and the ones holding the fort in our apartment. For the first time in his life, my father was staring at a scenario in which he could not protect his family. He had never imagined that, at sixty, and after a life of good health, the virus would leave him so unmoored from the role he had always played. That evening, as I was leaving to go to the pharmacy in the middle of the lockdown in Delhi, I remember looking back and seeing my father on the phone with his brothers. His voice was breaking as he pleaded for help finding a hospital bed for my mother. From the TV and from conversations with relatives, it had become clear that we were on our own. A dashboard run by the Delhi government showed vacant beds only in far-flung hospitals—makeshift COVID-care centers where a “bed” did not guarantee a working oxygen supply, a doctor, or the availability of a ventilator in dire situations.

Worse, news from the city’s hospitals was fast convincing people that a death at home might be more dignified than what awaited inside: being wrapped in plastic, taken away in PPE, and denied the basic privilege of a final goodbye. Families weren’t being privileged to even see the bodies of their loved ones before cremation. A relative who had returned after the funeral of his mother-in-law remarked that her pyre was burning with a dozen others at the same time in a busy crematorium in Delhi. “When we walked away after lighting it, we weren’t even sure which one was hers,” he said.

We administered many COVID-19 tests during the course of our illness—at home, and later in the hospital for my father. None ever came back positive. But the virus was destroying my parents’ lungs fast. On Day 11, when they were too sick to walk, we somehow managed to load them onto an e-rickshaw like rag dolls, and rode to a radiology center for CT scans. The results confirmed what we knew all along: severe COVID pneumonia.

During the chaos and carnage in Delhi, hospital administrations were creating labyrinths for the sick. Beds were a prized possession; ICU admission was not guaranteed, quality of care and other things were still afterthoughts. Doctors had a new challenge at hand: triaging. My father, on account of turning sixty in March, was a new entrant to the status of “senior citizen”—something that had helped him get the first dose of the vaccine in late March. That same status of seniority now threatened his life. To make matters worse, many hospitals we contacted were refusing admission to patients without a positive COVID test—so much so that the central government had to issue a revised national policy in May 2021 clarifying that a positive test result was not a prerequisite for hospital admission.

When my father died two months later, his death was no longer timely enough for the hospital protocol to be labeled as COVID-related. Since the infection had occurred much earlier, and his test had never returned positive, his cause of death could not—officially—be counted as a COVID-19 death.

Counting the Dead

Roughly 30% of deaths in India go unregistered each year. Minimal incentives, and poor access to death registration services, are the more obvious reasons for this data darkness. Deaths among rural populations, women, and religious or caste minorities are disproportionately under-registered. Healthcare institutions often lack the capacity to formally certify causes of death; many deaths take place outside institutional settings; and sometimes, as in my father's case, the timeline or documentation simply doesn't align with rigid protocols.

More importantly, cause-of-death certification itself remains rare. According to the Indian government’s 2021 Medical Certification of Cause of Death (MCCD) report, only 23.4% of all registered deaths in the country were medically certified. Before the pandemic, India recognized 19 official categories for causes of death. The most common causes were cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and infectious and parasitic diseases. In 2020, a new category was added: Deaths due to special purposes (COVID-19). But this category was used sparingly, and almost always only when a death occurred with a positive test result and (typically) within fourteen to twenty days of infection.

In August 2021, the Supreme Court directed the central government to expand its criteria for COVID-19 deaths, urging it to include cases like my father’s—where patients were admitted for the virus but died later from related complications. In response, the Ministry of Home Affairs clarified that any death within 30 days of testing positive—or clinical diagnosis—would be counted as a COVID-19 death, even if it occurred outside a hospital. The affidavit also stated that patients who died after being hospitalized for more than 30 days, under the same admission, would still qualify as COVID-19 deaths. For families who were not satisfied with the cause of death listed on official certificates, the policy included a provision for appeal.

These revisions were made primarily for legal purposes—to enable families of the deceased to access compensation of ₹50,000 (roughly $600). But there appears to be no mechanism to revise casualty numbers retrospectively, nor any drive to revisit medical certificates issued before September 2021. Limitations of state capacity may partly explain this, the result is a persistent and systemic undercounting of the dead. If these lives are unlikely to ever be formally acknowledged in public health records or policy planning, it becomes unclear how cities, states, and the country will ever learn to avert and reduce the impact of disasters and public health crises.

Official COVID-19 death counts are shaped by three factors: the availability of diagnostic testing, the robustness of health and civil registration systems, and the standards for certifying causes of death. Together, these constraints have contributed to a significant undercount of lives lost to the virus globally. To address these gaps, researchers often rely on excess mortality—the number of deaths that occurred beyond what would normally be expected based on historical trends. This metric captures both direct and indirect losses: people who died from COVID-19 itself, as well as those who died because the pandemic strained health systems and disrupted access to routine care. At the same time, excess mortality figures may be partially offset by deaths that were averted during lockdowns—like those from traffic accidents or hazardous jobs. The Civil Registration System (CRS) data in India shows that registered deaths jumped dramatically: from 7.64 million in 2019 to 8.12 million in 2020 and over 10 million in 2021, a surge of 2 million deaths in a single year. While annual increases due to population growth typically account for 1–2% change, the 2021 spike far exceeds those margins. The Medical Certification of Cause of Death (MCCD) data tells its own story. Between 2017 and 2019, deaths from “respiratory illnesses” (i.e. not COVID-19) rose steadily—by about 5 to 11% each year. But in 2021, the trend breaks. Reported deaths due to respiratory infections shoot up by a staggering 68%, many of which are widely understood to reflect COVID-19 deaths that were never officially attributed as such.

Harvard scientists—including some I’ve worked with—analyzed civil death registers from a sample of 90 municipalities across the state of Gujarat to estimate the true toll of the pandemic. Using weekly mortality data from January 2019 to February 2020 as a baseline, they measured excess deaths from March 2020 to April 2021. In that period, the state government officially reported around 10,000 COVID-19 deaths. But the researchers found over 21,000 excess deaths across just those 90 municipalities—a 44% increase over expected mortality. The sharpest spike came in late April 2021, when deaths surged by nearly 700% compared to normal.

But you didn’t need to be a Harvard scientist to sense the scale of destruction and death. At my father’s funeral, a distant cousin—still a farmer in a village in Haryana—remarked, quietly and plainly, that in every village, four to six people had died. There are 649,481 villages in India. Granted, they vary in size—but even if you multiply that conservatively by four, you arrive at nearly 2.6 million deaths. Roughly 65% of India’s population still lives in rural areas, and when you account for urban deaths as well, the total plausibly exceeds four million. It may be a back-of-the-envelope calculation, but no matter how you slice it, a truth emerges and a number writes itself.

Political Acts

Amnesia about the pandemic remains widespread—even though it may have killed several millions of people. The Indian government's response to the WHO’s estimate of 4.7 million excess COVID-19 deaths in the country has been one of outright rejection. When WHO released its estimate and accompanying methodology in 2022, it classified all countries of analysis in Tier I and Tier II. Tier I countries were those that provided complete, nationally representative, monthly all-cause mortality data. For them, WHO used actual reported figures. Tier II countries, including India, were those whose data was not fully available. In these cases, WHO relied on statistical modeling—drawing from available subnational data and extrapolating. In India’s case, WHO used data from 18 Indian states, covering approximately 70% of the population, to arrive at the national figure. India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and several state health ministers objected to both the tier chosen for India and the methodology, arguing that WHO failed to adequately consider India’s “authentic data” from its Civil Registration System (CRS), despite several attempts at correspondence.

But in 2025, newly released updates to the CRS somewhat confirmed independent estimates. Even after accounting for improved registration, demographic shifts, and annual variation, the math still points to a significant rise in mortality. Remember, only 23% of all registered deaths in India are medically certified. Yet, even within that limited pool, over 400,000 deaths were certified as COVID-19—already more than the government’s previously reported toll of 330,000 for 2021. If cause-of-death data had been recorded for all 10.2 million deaths in 2021, the number attributed to COVID-19 would almost certainly have been much higher. Many questions remain, especially now that the data source underpinning these revelations is the very one long advocated by the Indian government itself.

Political researcher Asim Ali has notes that even the colonial British government, in its 1880 Famine Commission report, was more forthright in acknowledging the scale of Indian deaths (about 5 million) under its own callous rule. Independent India, on the other hand, appears to have had little political incentive to pursue the truth.

It is unclear whether India—with higher resource burdens and the world’s largest population—will carry meaningful lessons from this pandemic into the next. There has been little pressure or any public reckoning over the (mis)handling of health and emergency response systems during the pandemic. The political imagination of the Indian electorate is consumed by unemployment, inflation, farm distress, and the promise of a functioning economy. In the neighborhood where we lived in Delhi, a helper used to wash my father’s car once in a while. Every time he washed the car, my father would give him a hundred rupees. When it had been some time since he had called him—on account of all of us being sick and quarantining—he walked into the house one afternoon, demanded work, and explained his brazenness: “Bhookhe marne se accha toh beemari se marna hai” (Better to die of disease than of hunger). That same sentiment—risking contracting the disease than dying of hunger—was echoed by informal workers across the world who had their livelihoods affected due to the disease.

The number of dead and aggrieved might well be in the millions, but in electoral terms, it is a diminutive number in India, which will never deliver electoral rewards or punishments. In 2020, just months after the initial lockdowns, a study published in BMJ Global Health analyzed survey data from India, the US, and the UK to find that voters were unlikely to reward or punish politicians for their pandemic response in upcoming elections.

In Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, viral images during the Delta wave showed bodies floating in the Ganga, believed to be corpses of COVID victims hastily abandoned. Some were buried in shallow sandbanks along the river, marked only by makeshift flags. For a brief moment, it felt like a national reckoning. But in the 2022 state elections that followed, COVID-19 did not register as a salient issue in the elections. A social worker who had volunteered to bury over 200 people who died from COVID-19 in Uttar Pradesh, risking his own life in the process, was interviewed by CNN in the days leading up to the election. He blamed lower-level officials, not the government, for the mishandling of the crisis, and said he would vote for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party for nationalistic reasons.

During the 1918 influenza pandemic—then referred to as the “Bombay fever”—the Ganga witnessed a similar tide of mass death. Historical accounts, including those by the Hindi poet Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’, describe how so many died—including his wife and several members of his family—that cities like Varanasi and Allahabad ran out of wood for cremation. He wrote of the Ganga as being “swollen with corpses”.

And yet, the 1918 catastrophe has largely vanished from public memory. This, despite the fact that it killed an estimated 6% of the global population, and led to the first—and only—census in Indian history where the country’s population declined. Despite it killing a staggering 12 to 13 million Indians, literature from the period offers only scattered traces of it ever happening. As the French historian Pierre Nora might say, there was no site of memory—no lieu de mémoire—to hold it in place. According to Nora, modern societies, in the absence of lived, embodied memory, substitute symbolic placeholders: museums, plaques, commemorations. But in India, even those proxies are often absent, and they continue to be in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though some things linger, even when their origin fades. The 1918 influenza pandemic significantly influenced the adoption of the handkerchief as a public health tool—coughs and sneezes were to be caught and contained. Today, the origin of that behavioral shift is mostly forgotten, but the gesture largely remains. The same may be true of the pandemic of our lifetime. COVID-19 may eventually recede from collective memory as a mass-death event. But certain shifts might outlive the memory itself. Remote work, for one, has become a permanent option for hundreds of thousands of white-collar workers who once commuted or relocated for their jobs. The pandemic also accelerated screen time and deepened digital dependence, pushing many further into cycles of distraction, fatigue, and addiction.

Acts of God

Words seldom offer comfort in the immediate aftermath of a loved one’s death. Generalities, or lessons drawn from another death, rarely soothe us in the face of a personal loss. As E. M. Forster wrote in Howards End, “one death throws no light on another.” Still, people try to say something to help make sense of the world after an unfathomable tragedy. It is almost inevitable that those words so often become banalities. When you’re a man—the man—the only surviving male in the household, elders will remind you, in many banalities and with a grave and dutiful tone, that the baton has now passed to you. (This, despite the fact that the women in my family have always had a far better repertoire of care, strength, and resilience.) The banalities that were particularly irksome in the aftermath of my father’s death were those laced with karmic justifications, divine will, and God’s plan. Karam and bhaagya. The implication (though softly delivered) was that his death was part of some grand cosmic accounting, and that he, or someone in his life, must have done something to deserve this much.

The idea of illness as punishment is among the oldest explanations for suffering. Epidemics, especially, are often framed as acts of divine wrath. Marie-Hélène Huet, who studies contagion and catastrophe in modern political thought, brings into focus the 1755 Lisbon earthquake that marked a turning point in Enlightenment Europe. Where once disasters were interpreted as divine punishment, the Lisbon quake shifted the intellectual response toward human responsibility. This shift, from divine to human responsibility, marked the beginning of a modern political consciousness. It demanded accountability from individuals and institutions, not just repentance from the people.

In India, mythology and modern life are often intertwined and coexist. Epidemics, in many Hindu worldviews, are not just biomedical events but moral and spiritual disturbances—consequences of collective karma or deviations from dharma. Illness can be a punishment for the crimes of ancestors or the transgressions of society as a whole. Hindu cosmology is cyclical, divided into four ages (yugas) that repeat over time. The current age, Kaliyuga, is believed to be the final and most degenerate—marked by moral decay, spiritual decline, and societal disorder. It is not uncommon, even today, for people to explain the chaos of the COVID-19 pandemic—fake medicines, hoarding and gouging oxygen cylinders, societal abandonment—as evidence that we are deep into Kaliyuga.

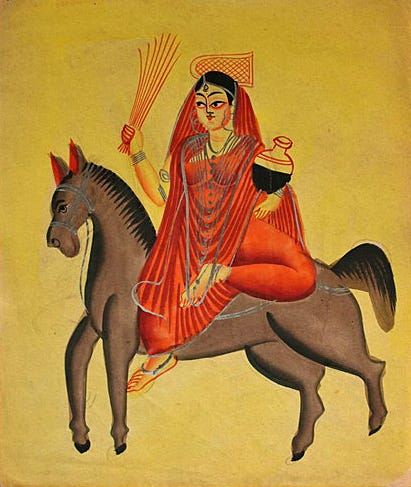

In folk traditions, disease was also personified. Shitala Mata, worshipped across North India, and Mariamma in the South, were goddesses of infection and fever. Plague, cholera, and pox were divine warnings. People held night vigils, sang bhajans, and offered food to appease gods and goddesses.

Illnesses have also been intimately tied to notions of purity and pollution—often leading to the ostracization of infected individuals, and especially those from already marginalized groups. In the medieval ages, Jews were often blamed for outbreaks of plague in Europe, accused of poisoning wells or spreading disease through sorcery. These allegations often led to violent pogroms and mass expulsions.

As Susan Sontag wrote, there is extraordinary potency in the metaphor of the plague. It is often imagined as something carried in by the foreigner, the outsider and the Other. It stands to punish the ‘innocent’ and the ‘pure’.

In the early days of the pandemic, Indian news channels found their scapegoats in Muslims. At the center of the communal frenzy was the Tablighi Jamaat, a Muslim missionary group that had held a gathering in mid-March 2020 at its global headquarters in Delhi’s Nizamuddin Markaz. Thousands had come from across India and abroad, and after the event, delegates—now dispersed—began to fall sick. Indian officials scrambled to trace and test attendees. By late April, the gathering had been linked to more than 4,000 cases. The communal reaction was swift. Many politicians and media loudmouths were quick to call it an “Islamic insurrection” and “corona terrorism.” Hashtags like #CoronaJihad trended on social media. Residents’ Welfare Associations in Delhi issued diktats barring Muslim vendors from entering their neighborhoods.

Blame, during and in the aftermath of disasters and pandemics, can be a rational exercise. It helps us draw lessons and hold the right people accountable. At its core, blame is a form of pattern recognition, a human impulse to make sense of chaos. For many, the pandemic became a tool to reinforce existing communal biases and discriminatory thinking. For others, blaming individuals in their immediate lives rather than governments or systemic failures, offered a more accessible, less overwhelming target, conveniently sparing the state from deeper scrutiny.

Tainted Lives

In Illness as a Metaphor, Susan Sontag writes that we all hold dual citizenship: one in the kingdom of the well, and the other in the kingdom of the sick. We all prefer to travel on our better passport, but crossing the border is inevitable. It might be a brief illness. Or a chronic one. Or the illness of a parent, a partner, a child.

It’s undeniable that our lives have been tainted by the pandemic. And any hope of healing begins, I think, with the quiet recognition that we must sit with our tainted lives and try, somehow, to make peace with them.

Sometimes, metaphors and casual remarks have a way of making you feel as if society is quietly arrayed against you. As a graduate student living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I struck up what felt—at least to me—like an unlikely friendship with a sixty-five-year-old man named Todd. Todd sat behind the cash register at a local hardware store. I had a habit of locking myself out of my house, so getting duplicate keys made me a frequent visitor. Once we started talking, I began stopping by just to say hi on my way home.

When I had to get a mandatory vaccine booster before returning to campus, I mentioned it to Todd—which quickly prompted an anti-vaccine monologue. Sensing that the conversation was heading somewhere unhelpful, I decided to tell him the truth about my father and that I had lost him during the Delta wave. The first question Todd asked—upon hearing that my father had died—was whether he had any comorbidities. When I said he didn’t particularly have any, Todd simply wouldn’t believe it. He insisted that only the very old or already sick could have died from the virus.

Too quickly, people decide that the dead were disposable. Risk group, a bureaucratically neutral-sounding category, is easy to assign in hindsight. In a post-hoc narrative, it’s convenient to assume someone must have belonged to it. Against this, it feels almost too small, too humiliating, to point out that my father exercised every day, did yoga religiously every morning, and had reversed his pre-diabetic status in his late fifties with discipline and support from his children. But of course, none of it matters. He is dead. I cannot negotiate out of that reality.

Once in a while, friends say something offhand in conversation. A friend I met for coffee in the U.S.—sixteen years after we’d last seen each other in middle school—remarked, with a shrug, that the pandemic was “good in some ways,” because India was “overpopulated.” In the years of our incommunicado, he had no way of knowing what the last four years had held for me. And his dark humour definitely needed a softer landing. In moments like these, you have a choice: reveal that you’re tainted and run the gauntlet of the bereaved, or stay hidden. I chose to say it—my father died of COVID. There wasn’t much left to say for either of us after that.

And then, sometimes, you’re offered extraordinary ways of spotlighting your grief.

In 2022, Dr. Satchit Balsari, a professor at Harvard Medical School, led a research initiative in Gujarat examining how the pandemic reshaped the lives of the working poor. Beginning as a traditional impact assessment led to the creation of a multimedia exhibition titled Hum Sab Ek (We are One) which has since travelled several cities and universities.

Drawing from oral histories and a survey of thousands of women belonging to the six-million-strong Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), Hum Sab Ek presented stories of hardship, adaptation, and survival during the pandemic. In many ways, it upended the skewed narratives that dominated public discourse and brought forward the realities of the common Indian. What was it like for a home-based worker to be locked in with an abusive partner? What was it like to step outside for groceries and be met with police batons? And more importantly: in the absence of functioning systems, where did people turn? How did they lean on each other?

The exhibit sought to recenter lives too often erased by headlines, hashtags, and datasets. I had the privilege of contributing to the research and editorial arc of Hum Sab Ek, helping shape which narratives were lifted—and how.

But stories of resilience often have to be sanitized, stripped of the harder truths, like death. At the launch of the exhibition, during a panel with the students who had worked on it, I casually mentioned my father’s death while explaining my own vantage point. I still remember the eerie silence when the truth landed. To soften it, I invoked Svetlana Alexievich’s approach to oral histories: how truth does not emerge from a single authoritative narrator, but from the collective hum of memory. And in a world where no one person can be neatly blamed, preserving grief becomes its own quiet act of justice.

Guilty Remnants

My father was always a good driver—so much so that there was never any real motivation for me to learn how to drive as long as he was around. In his youth, he had always ridden a motorbike. At the age of twenty-eight, in preparation to marry my mother, he was told he would receive a Fiat car in dowry—then the only car commercially available in India. To claim it, he practiced for a few hard weeks and managed to get his license just in time for the wedding.

Over the years, we remember fondly the long road trips from Delhi to the sand dunes of Rajasthan, and along the serpentine roads of the Himalayas. As children and later as adults, we rode with him across India’s chaotic roads in the modest vehicles he owned throughout his life: the dowry Fiat, his Maruti Suzuki 800, and eventually the humble WagonR. Fiercely defensive, meticulous behind the wheel, he was always sharp and always in control. After retiring from the Haryana government, he found a particular joy in driving my mother and sisters to their workplaces. He also enjoyed the wide avenues of New Delhi and had endless patience for its traffic. He absolutely loved being a provider, even though he’d officially stopped working.

One of the first things he did after retiring was insist on teaching everyone in the family how to drive—passing on his astute skills to us. But he was a tough teacher and hard to impress. My sisters and mother quickly opted out of his lessons, preferring the gentle nudges of driving school instructors instead. As a fellow man of the house, that kind of cop-out would have been too much of an affront for him. So I obliged. But I was a bad driver.

A few months before we got sick, we were out on a practice drive. Climbing the ramp to a flyover, I slowed on an incline and didn’t pull the handbrake in time—we rolled back and hit the car behind us. What followed was almost a caricature of Delhi road rage: the other driver got out, hurled a volley of unkind and graphic expletives, and began slamming on our windshield, demanding that we get out of the car. In my own performance of Delhi bravado, I fought back and nearly got into a physical altercation, grabbing the man by the collar. My father had to step in to de-escalate and mediate.

When we finally drove off and I tried to lighten the mood with a joke, my father didn’t laugh. He stared straight ahead at the road and simply said, “There has to be a deadline for when you’re as good as me at driving—because I’m getting old.” I was upset. We argued a little, because it felt like a passing of the baton. And I wasn’t ready for it. I wasn’t supposed to be ready. He was always supposed to drive us. That’s how it had always been.

Nonetheless, I asked him an objective question—wanting to know how much time I had to perfect his swivel through Delhi’s circuitous, clogged roads. He looked ahead and said to me, with finality in his voice: “Twenty-eight. That’s the age I learned to drive to earn your mother’s hand.”

In late April, while I was out buying steroids and nebulizers—our last-ditch attempt to keep our parents from being hospitalized—I got a call from my sister. Dad’s oxygen levels had dropped into the low sixties, and my mom’s were hovering in the high seventies. In a state of panic, we turned to our cousin Aman, a doctor at a government hospital on the outskirts of Delhi. He said he could somehow arrange a bed—but only one. That ruled out any possibility of treatment for both of our parents. We had to choose. And we had to pick one of our parents up and get them twenty-seven kilometers away, across the Yamuna river.

I had the car keys in my hand, a 103-degree fever, standing at the precipice. But the baton, as it turned out, could not be passed on to me. My father was already gasping for breath. I was too sick and too scared to risk putting all of us in jeopardy. And most of all, I was paralyzed by the fear that we could lose both our parents—my father on the way to the hospital, and my mother left alone at home. A kind autorickshaw driver, seeing our panic in the street, agreed to take us.

I am twenty-eight now. In less than a week, I will be twenty-nine. The deadline my father set has come and gone. I am not a better driver. In fact, I’ve willfully forgotten the skill. And here too, I’ve chosen amnesia over the unbearable truth.

In Tom Perrotta’s 2011 novel The Leftovers (later adapted into an HBO series), a rapture-like event causes 2% of the global population to suddenly vanish. Those left behind are plunged into existential confusion, grief, and a deep need to make sense of what happened. Among them emerges a cult called the Guilty Remnant—a group of white-clad, chain-smoking, silent adherents who renounce all earthly attachments and pleasures.

The Guilty Remnant believe the world ended when those people disappeared, and that it is absurd—offensive, even—to pretend otherwise. They refuse to speak, wear white as a constant visual of mourning, and chain-smoke to harm the body and reject the sanctity of life. They follow people, hold up signs that say “Don’t Forget,” and sometimes trespass into homes to stage unsettling tableaus of loss.

We forget to cope. Years passed give us an altitude. With a bird’s eye view, four years into the biggest tragedy of your life, it is easier to see the devastation. And in bursts, you remember: something so foundational to your existence has not changed another person’s life—not even a little bit. Out of guilt, or rage, or some twisted hope, you begin reminding them. You want to take them by the elbows and scream into their ears: Don’t you see how we are hurting?

A few weeks ago, my mother visited me in America—a twenty-four-hour journey that worried her children sick. In an ideal world, one where my father was still alive and healthy, she would have leaned on his quiet wisdom, and he would have relied on her street-smart instinct. Instead, we sat oceans away, imagining her making her way alone through the airport during a layover, trying to navigate the circuitous immigration process, struggling to connect to Wi-Fi. He would have been there to guide her hands if she failed. In the end, she made it from Delhi to Boston without incident. But when I came to pick her up at the airport, her tiredness and quiet loneliness landed harder than our worries. Sometimes the fear of being orphaned is so consuming, that it eclipses the grief of losing one parent.

So how does one go on—how does one live with this and also go on breathing? On the fourth anniversary of his wife’s death, British author Julian Barnes wrote, “If I have survived what is now four years of her absence, it is because I have had four years of her presence.” Sometimes, we honour the dead by becoming them. Other times, we live in quiet gratitude, feeling joy at the blessing of their soul, and awe at the spellbinding nature of their brief and miraculous lives.

My sister Yasha, who recently became a mother, says life keeps her so busy now that she’s forgotten how to cry when she remembers Dad. “I have so much newfound appreciation for Mom and Dad after becoming a parent,” she tells me—assiduously cleaning, feeding, dropping my niece off at daycare. A lifetime of it, she imagines, is the most selfless thing that one human can provide to another. There’s no badge or honor you get for it either. You just hope, selflessly, that your children are loved, and grow up to love their lives. “And then,” she says, “I feel proud that Mom and Dad were able to do it, you know? Despite everything life threw at them?”

In moments of frustration—when life gets to her, when she’s reminded that her daughter will only ever know her grandfather through a photograph and not his illuminating presence, his unique sense of humor, his tickles and silly quirks—Yasha says, “In those times, I hate fathers altogether. And I hate people whose fathers are still alive.” But then, she says, there are moments when she sees others stepping up—fathers showering their children with love, tenderness, presence. “It gives you hope, you know?” That somewhere, this selfless love is still alive between parents and their children. And that hope, however small, helps you hold the world in a better light. It defeats, if only for a moment, the darkness that life has given you.

She pauses—on the verge of crying, despite having just claimed she’d forgotten how.

“There was a time,” she says, “when Mummy was in the hospital and you were the one being taken care of.”

My mother had been hospitalized for several weeks after a complicated surgery—the one that brought me into the world. “Those weeks, I will never forget,” she continues. “He used to bathe us, iron our clothes, dress us for school, and prepare our tiffins—always overfilling them beyond our appetites. In the evenings, we would visit you and Mom in the hospital, and then go home, where he’d feed us again and read us stories before bed. It was a strangely joyous time—a soft, golden memory that has stayed with us like a blessing.”

“I wish people could know all of that, you know?” she says. “I wish they knew what kind of man he was—his simple gestures, his quiet wisdom, his everyday devotion. All of it counted, you know?”

Here was a man we loved. Here were the precious gifts of his life. We remember and celebrate them now. All of them counted.

Kartikeya, I'm deeply sorry for the loss of your father. I hope you and your loved ones continue to channel the grief through the resilience and fortitude you have displayed so far.

I must also thank you for the writing this deeply moving essay. In the end, the love and care we inherit from our parents is the biggest legacy we can uphold and passing it to others is a befitting tribute in itself.

Kartikeya, thank you for writing this moving and thought provoking article. It really makes me think about the importance of collective memory, and what we do to the survivors as well as to future generations when we allow ourselves the comfort of amnesia. What did we learn from this tragedy?

Personally grateful for your sharing your story so honestly and beautifully. We will all join you on the other side of this grief eventually. I am so sorry that you were forced there so early by life. I want to send my love to your sisters as well.

You introduced a lot of very intriguing ideas - about blame, survivor's guilt, collective memory, counting the dead, and made me really wonder what further thoughts you may have on their implications. Hope to hear more from you if it's a direction you choose to go in.